- Home

- Andrea Pinkney

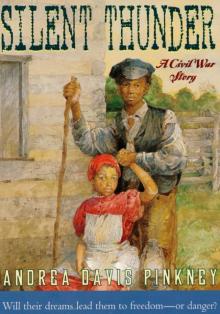

Silent Thunder Page 7

Silent Thunder Read online

Page 7

The twilight sky was turning from black to gray. The sun’s crown lit the horizon. Chief crowed. Our lesson time was almost over. “When, Ros,” I said. “When we goin’?”

“Soon,” Rosco said, looking off toward the fence near the toolshed, the place where Chiefs call was piercing the morning’s quiet.

“Folks’ll be rising soon. We ain’t got no more time for letters today, Summer,” Rosco said.

Using the tip of Walnut’s leg as my quill, I’d already written my name on the dirt strip between us. And I’d drawn a flower next to it.

Rosco picked up a sharp twig, and wrote two words after my flower: promised land.

I leaned in toward the dirt to get a good look. I sounded out the shorter of the two words. “Land”

Rosco nodded once. “Land,” he repeated.

Then, as he did at the end of every lesson, Rosco smoothed fresh dirt over my writing and his, then tamped the dirt with his palm. And, like always, he threw down a patch of his spit to wet the dirt, and tamped again. “We best be gettin’ on, Summer,” he said. “A new day is coming.”

14

Rosco

November 18, 1862

I’ll meet you in the mornin’

When I reach the promised land;

On the other side of Jordan,

For I’s bound for the promised land.

“OLD CHARIOT,” THEA’S HYMN, the one she leads off singing after evening prayers in the quarters, wouldn’t leave me alone. That tired song had been grinding in my thoughts ever since Clem told me he was runnin’ North. Today, when I was bringing Marlon back to the stables after a ride in Parnell’s meadow, “Old Chariot” wouldn’t quit haunting me. I did everything I could to push that hymn away. Even Marlon’s ornery gait didn’t help. Neither did the pounding of Clem’s mallet shooting up from the smithing shack on the other side of the stables, where Clem was shoeing Dash.

With Parnell being sick, I now had me two horses to care for. There was Dash, Lowell’s spotted mare, and Marlon, the master’s own bay gelding. I’d always done the dirty work of tendin’ to Marlon—mucking the stalls and such—but it was the master who worked Marlon’s gait. Before Gideon got sick, he was the only one who rode Marlon. Now I was the only one who rode him.

I’d been tendin’ horses since I was old enough to shovel hay, and I hadn’t ever seen a cranky cuss of an animal like Marlon. Marlon was as stubborn as they come. And he was a big horse, sixteen hands high. There was a lot of him to put up a struggle.

I stood at the stable gate, yanking on Marlon’s rein, trying to return him to his stall. “C’mon, Marlon.” I clucked my tongue, but Marlon wasn’t budging.

“Horse,” I said, “stop actin’ like a mule!”

Marlon reared his head.

“That’s what I said— mule.”

Marlon crunched the hay under his hooves. It seemed he was thinking about his next move. This time he inclined his head toward the stall, like he was trying to show me something. Then he sputtered his horse lips, right at me.

“I been in that stall a million times, mule,” I said. “All that’s in there is hay and the smell of horse pucky. Ain’t nothin’ new, so git on in.” I gave Marlon’s rein another tug. But Marlon stayed put.

I could feel my temper starting to flare. And to make the whole stubborn situation worse, Thea’s hymn was back at me again:

When that old chariot comes,

I’m going to leave you,

I’m bound for the promised land,

Friends, I’m going to leave you.

I let up on Marlon’s rein, and gave in to “Old Chariot.” I sang the next verse, hoping that by letting the song spill from my lips, I could somehow set it free from my thoughts.

“I’m sorry, friends to leave you,

Farewell! Oh, farewell!

But I’ll meet you in the morning,

Farewell! Oh, farewell!”

Marlon nudged my shoulder with his muzzle. He sputtered his horse lips a second time. I couldn’t help but giggle. “You like my singing, huh?” (Fact is, most stubborn horses took to singing. ’Least I’d found that to be true.)

I obliged Marlon with the same verse again. Every time I sang “Farewell! Oh, farewell!” Marlon’s hooves crept toward his stall. I let the final “farewell” go for several beats—farew~e~l~l—until Marlon had his whole front inside. There was no need to keep yanking on his rein. All I had to do was keep singing. So I did.

Slowly, Marlon made his way into his stall. But at the fifth farw~e~l~l, he stopped again suddenly. The ping of Clem’s mallet was going at a steady slam. I tried to calm Marlon. “That noise ain’t meant for your shoes,” I said. “Don’t let it fret you, now.”

Marlon inclined his head again. I looked in the stall, thinking maybe he’d seen some kind of jumpy shadow. But it wasn’t a dancing black light that halted Marlon. It was young master Lowell, peering through the stable slats from outside. All I could see of him were his eyes and brows, and the bridge of his nose. He was darkened in shadow, but he remained very still. It startled me all the same.

He spoke softly. Without blinking, he said, “You sing good, Rosco.”

I eased backward, feeling Marlon’s breath at my ear. My insides were thumping faster than moth wings near a flame. “Master Lowell?”

A kindly expression rested in Lowell’s eyes. And he was looking at me in the same glad way I seen Mama look at a bud from Missy’s garden that has blossomed overnight.

“Master,” I said, “there’s a chill out here. What brings you?”

Lowell spoke softer still. “I was looking to get some air, and I heard your singing,” he said. “Can you teach me? Teach me to sing?” Now Lowell looked expectant.

I shrugged, then moved closer to the stable slats to match my eyes with Lowell’s. Marlon must have been comforted by our closeness. His rein gave some slack, and I felt his big brown body give a little, too. He stepped fully into his stall where he belonged, right behind me. I could still feel his horse breath next to my ear.

“Singing ain’t nothin’ to learn,” I said to Lowell. “You just do it.”

Lowell said, “Not if you’re cursed with a timid soul, like me.”

Lowell and I watched each other for a long moment. The only sound between us was the swish of Marlon’s tail slapping a fly that was bobbing at his hindquarters.

Finally, I spoke. I said something I’ve heard both Thea and Mama say many times. Now I was saying it to Lowell. “When the soul grows timid, faith will lead the way.”

The late afternoon sun was beginning to bend its limbs toward the stables. A slant of light came around Lowell’s face, through the slats. I squinted back the glare, which was settling on my face.

Lowell reached a hand through the slats, into the stable, and set it gently on Marlon’s face. He started to sing, soft and slow.

“I’ll meet you in the mornin’

When I reach the promised land. . .”

Lowell’s voice was no more than a whisper. Marlon’s horse lips were at it again, blowing out small sputters. After two lines of song, Lowell stopped. “That’s all of the hymn I recall, Rosco,” he said, stroking the white star along Marlon’s nose.

I recited the rest of the first verse, my eyes never leaving Lowell’s. He then sang each word with steady, gentle conviction.

“On the other side of Jordan,

For I’s bound for the promised land.”

When he was done, he said, “That’s a fine song, Rosco.”

“You the one who makes it fine, by the way you sing it,” I said.

Another silence came between us. A silence different from before. It was a pleasing stillness. I was taking comfort in Lowell’s company, in the natural way he was speaking to me. I couldn’t help but enjoy the ease of it.

Now the sun was playing at Marlon’s feet. Then Lowell came ahead with a sudden question. He lowered his voice, deliberately this time. He spoke with the understanding kindness of a brother. “

You can read, can’t you?”

I licked my lips, and groped for Marlon’s rein.

Lowell said, “When the soul grows timid, faith will lead the way.”

Right then, something in me let go. But I didn’t let my eyes drop—I just couldn’t look away. I nodded once, without answering.

More of Clem’s pounding flung out from the smithing shack.

15

Summer

November 22, 1862

MAMA AND I WERE PREPARING a supper tray to take to Master Gideon in his study. My job was to set the tray with its linens and flatware while Mama made Master Gideon’s supper. (She had to mash his food so’s he could swallow it easy. She mashed every morsel with the exactness deserving of a baby’s food.)

I was just not moving fast enough for Mama. Everything I did was wrong. When I took my care in folding the master’s napkin and positioning it on the tray next to his plate, Mama came at me like a slap. She said, “I got a mind to shake you, child. Stop dawdling.” Then she peered at the napkin on the tray. “The master don’t like all that fancy folding. Just set the napkin by the plate.”

I sucked at my teeth. “The master’s got bigger problems than his napkin,” I said.

Mama was standing by the window, her back to me. “Cut your sassin’,” she snapped.

Since Mama wasn’t lookin’, I folded the napkin double.

Something in me shivered right then. An ugly thing was flaring between Mama and me. We’d had our differences, but now we were exchanging the clipped, angry words of true enemies, and it hurt.

With Mama’s back still to me, I could see her shoulders tense beneath her dress. She turned to the larder, to the place where she kept the little pouch of head powders Doc Bates had prescribed for the master to stir into his tea. This was always the last item Mama put on Master Parnell’s tray before taking the tray to him. The head powders were the only thing that brought the master comfort these days. Without the powders, the master’s supper tray was incomplete.

Mama looked for the powders busily, sinking fully into the distraction they offered from me. The pouch of head powders stood in plain view on the windowsill, next to a pouch of sugar for tea. Both them pouches looked like one and the same. The only thing that set them apart were their marker labels.

Mama turned away from the larder. She put her hand to her cheek, pressing her memory for where the head powders might be. I could see frustration budding on her face. The larder stood open behind her.

“Look to the sill, Mama,” I said simply.

Mama’s eyes shot to the sill. Now her expression was clouded with a mix of relief and exasperation. Her jaw went tight. Her eyes flew from the two pouches to the master’s tray, then landed square on me. “Which one’s the head powders?” she asked quietly.

“The one nearest to the pie you set out for coolin’,” I said.

Mama lowered her eyes. She put the medicine pouch on Master Gideon’s tray, then lifted the tray in front of her. “Well, then,” she said, “I best be gettin’ to the study.”

16

Rosco

November 25, 1862

CLEM WAS NEARLY INVISIBLE. Even with his skin as black as it was, I could barely see the likes of him. The morning was thick with a fog like I ain’t never seen before. A fog that spread its gray-white cape over every inch of Parnell land. Clem sat at one end of a fallen tree trunk. I took my comfort at the tree’s other end, a hollow filled with leaves. I could make out the contours of Clem’s shoulders, back, knees, and hands, but the rest of him was steeped in the haze.

This was my favorite kind of Sunday morning, the kind that asks little of you. We’d seen the Parnells off to church and could now enjoy a bit of what we Parnell slaves had come to call “wearing the day like a comfortable set of clothes.” (Even in his condition, Gideon attended church services. Missy Claire believed that if he accompanied her and Lowell to “the Lord’s rightful house,” it would help heal him.)

Clem took in a weighty breath. “Come Christmas, I’m gone,” he said. His words were soft and far away. He wasn’t talking to me. It seemed he was speaking his thoughts.

He snapped a twig from his side of the tree trunk and began to tap out a random beat. The sound came slowly, a flat, lifeless clap. “The night sky’s clearest in winter,” Clem said. He was still talking to the fog. “When the sky’s free of clouds, there ain’t no trouble findin’ the Diamond Eye.”

I wondered if I was as ghostlike to Clem as he was to me. “What’s the Diamond Eye?” I asked.

“That’s what my Marietta used to call the North Star, the star that points the way to freedom.” Clem went back to stilted beats with his stick.

“How you supposing to get gone, Clem?” I wanted to know. “You gonna run off, same way you did with Marietta?” I asked cautiously.

Now Clem was beating the tree trunk with careful, rhythmic precision. He let loose with the rattly sound of wood slapping wood. He jerked his head to the beat of his own music. “Gettin’ North on foot ain’t the best way,” he said. “This time, I’m hitch-ridin’ to freedom. Gonna let some kindly white folks take me for a ride.”

I slid closer to Clem. My own head was getting caught up in the tempo of his sticks. I started to nod with the beat, which was strong and steady now.

Clem rolled out a plan. A plan that was as solid as his tree-drum. “Not every white man is pushing along with the wheels of slavery,” he said. “Some think it’s downright evil, and them’s the ones who have gone and set up a way of helping the likes of us go North. If you and me want to enlist in the Union army, we got to get to Baltimore, then to Philadelphia, then to Boston—on rides in the white man’s wagon.”

“You talking ’bout the freedom trail, ain’t you?” I asked “I been hearing about them night rides in the backs of wagons, ducking and hiding in ditches and hovels all with the help of them whites folks who been calling themselves abolitionists.”

Clem stopped with his sticks. He struggled to repeat my word.

“Ab—abol—abolitionist,” he said finally. “Right, them’s the ones I’m talking about.”

We sat quiet for a moment. The fog began to lift its cape. “Remember what I said about Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation that night in the quarters, the night Parnell had his stroke?” I asked.

This was one of those questions that gave Clem pause. He scratched his stick against the tree trunk’s bark. He didn’t answer me right off. Then he said, “Yeah, I remember. And since that night when you spoke on it, I’ve caught talk of it in town.”

“What talk?” I asked.

“Some talk,” was all Clem said.

I told Clem all I knew about Abraham Lincoln’s draft of the Emancipation Proclamation, how it had been presented to Congress, and how the president was planning on issuing the final and true document at the first of the new year. “If it passes, we’ll be free,” I explained.

“If. That’s what they been sayin’ in town about this proc—proc—proclamation, that it’s all a big ol’ if.” Clem shrugged. “I can’t be sittin’ around waiting for an if to happen,” he said, shaking his head. “When me and Marietta were plannin’ to jump the broom, I spent night after night thinking on how fine life would feel if we could be together. And what a glad day it would be if we could get us our own place near the quarters, and start us a family.

“And I kept telling myself that maybe, just maybe, I could find a little piece of happiness livin’ here on Parnell’s plantation— if Parnell bought Marietta so’s we could get hitched.” Clem shook his head. “My if’s were all about hope back then,” he said softly.

I nodded, remembering how giddy-in-love Clem had been with Marietta.

“Now,” Clem said, “all’s I think about is what if Marietta’s hurtin’ somehow, wondering why I ain’t come to find her. What if she’s gone and fell in love with somebody else? And what if cotton country has worked her to weariness?”

Clem looked off toward the far meadow. “If ain

’t nothing but a bushel of disappointments,” he said. Then he snapped his drumming twig in two and flung it to the woods.

“Freedom’s ours for the takin’, but we gotta take it soon, before Missy’s South-lovin’ brother gets here.” Clem’s words were clenched with determination. “You comin’ with me, or you staying back to wait for Mr. Lincoln to make up his mind?” he asked.

Even with all my itching to enlist, I still wasn’t so eager to follow Clem. I had a small faith in our president’s proclamation, but I couldn’t share my hope with Clem. He’d lost all faith in any kind of good. “I need to think things through, Clem,” I said.

“What’s there to think on? You want to fight for freedom or not?”

Clem was pressing at me hard. I could feel myself growing fidgety. “What kindly white men live around here who are gonna help nigras get free?” I asked. “This land’s full of Secesh. Probably ain’t even a single abolitionist within a hundred miles,” I challenged.

“I know me one man who’s on our side, and that’s all I need to get gone,” Clem said.

I wondered if Clem was talking truths or just fronting, trying to sound like he knew it all. “Who is it, then?” I wanted to know.

“It’s the master’s own medicine man, Doc Bates, that’s who.”

17

Summer

November 30, 1862

ON SUNDAYS, THEA LEAD A sunset worship service for us at the meeting quarters. She began this evening’s service asking us to each bow our heads, and to make an appeal to the Almighty. Tonight she spoke with true conviction. “Someone among us is suffering with the pain of a long-held secret,” she said. “If each and every one of us prays rightly, that soul’s hurt will be healed by the Almighty’s powerful hand.”

Thea sure couldn’t have been talking about me. The only secret I had was learning letters, and that wasn’t even a secret, really. Thea, Mama, and Rosco know all about my letter learning. I had me a lot of hurt that needed healing, though. The strain that had come between me and Mama was fixing itself all the way to my bones.

Silent Thunder

Silent Thunder