- Home

- Andrea Pinkney

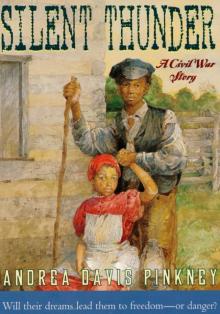

Silent Thunder

Silent Thunder Read online

SILENT THUNDER

A Civil War Story

ANDREA DAVIS PINKNEY

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to the following organizations and individuals for their research assistance: Chelsea Equestrian Center; The College of Physicians Library, Philadelphia; Julius Lester; Caroline Duroselle-Melish, reference librarian, historical collection, the New York Academy of Medicine. And last, but certainly not least, I owe tremendous gratitude to my editor, Donna Bray, and to art director Anne Diebel, both of whom brought incredible brilliance and professionalism to the creation of this book. Thanks, too, to Jerry Pinkney for a stunning jacket.

First Hyperion Paperback Edition 2001

Copyright © 1999 by Andrea Davis Pinkney

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information, address Writers House LLC at 21 West 26th Street, New York, NY 10010.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Pinkney, Andrea Davis.

Silent thunder: A Civil War story /Andrea Davis Pinkney.—1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

Summary: In 1862, eleven-year-old Summer and her thirteen-year-old brother Rosco take turns describing how life on the quiet Virginia plantation where they are slaves is affected by the Civil War.

ISBN 978-0-7867-5365-9

I. Virginia—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Juvenile fiction. [I. Virginia—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Fiction. 3. Slavery—Fiction. 4. Afro-Americans—Fiction.

5. Underground railroad—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.P6333Si 1999

[Fic]—dc21 98-32071

Distributed by Argo Navis Author Services.

To Lynne and P.J.

Contents

Part One: Trumpets of the Sky

1: Summer

2: Rosco

3: Summer

4: Rosco

5: Summer

6: Rosco

7: Summer

8: Rosco

9: Summer

10: Rosco

11: Summer

Part Two: Serendipity

12: Rosco

13: Summer

14: Rosco

15: Summer

16: Rosco

17: Summer

18: Rosco

19: Summer

20: Rosco

21: Summer

Part Three: Old Chariot

22: Rosco

23: Summer

24: Rosco

25: Summer

26: Rosco

27: Summer

28: Rosco

Epilogue: Rosco

A Note from the Author

Bibliography

PART ONE

Trumpets of the Sky

1

Summer

August 21, 1862

EVERY YEAR WAS THE SAME. Come my birthday, he beckoned for me. He called for Rosco on his birthday, too. But Ros, anytime I raised it with him, he wouldn’t speak on it.

Mama always made me wear my best—the calico dress she sewed for me to wear to Sunday services— and she scrubbed me till even my toe jam came clean. And Mama’s orders to me never changed: “Don’t go pestering him with all your foolish questions. And remember your manners.”

Then she took me to the master’s study, where she presented me to him. “Summer’s come,” she said simply. But even in her plain way of talkin’, Mama put me in front of the master like she was making a proper introduction.

I’d been having these birthday look-sees in the master’s study for as long as I could remember. But every year—my birthday was the only day Master Gideon Parnell ever spoke to me—Mama presented me to the master as if he were meeting me for the very first time. Then she quickly left the study, carefully closing the large double doors behind her.

Master Gideon was seated at his desk. He looked as if he’d been waiting for me. “Come closer, Summer. Let me have a look at you.” I made my way in slowly. He was nodding approval as I approached. I stopped just short of his desk chair. I suddenly remembered my manners, and gave a little curtsy. It was early morning, so the day’s heat had not come on fully. It would come, though. Would come strong. Today the swelter seemed to be starting up in me, before it had poured over the air outside.

I’d been in Master Gideon’s study plenty of times. Mostly, though, he wasn’t in there when Mama and me were cleaning. There was something different about that study when the master was inside. He filled it somehow. Filled that place full of polished mahogany and heavy curtains. He made that dark, serious room get to be alive and breathing.

As I stood real still, waiting for Master Gideon to speak, he slowly lowered his eyes over the top of his reading spectacles. “You’re getting to be a fine young lady, Summer. Girlhood’s soon to be a memory to you,” he said.

“Yessir.” I smoothed my dress.

Seeing as the master didn’t hardly pay me no attention any other time, I used these birthday visits to steal a close look at him. There was something in the master’s face that tugged at me. Something that made me want to hang on when I looked at him. Seemed like I was always about to find something when I got to studying hard on his face. Could have been I felt that way ’cause the master’s eyes didn’t hardly leave mine whenever I went to him on my birthday. It was as if I were tugging at him, too. It was as if he were searching for a lost thing when he looked at me.

“Your mama ever tell you how you came by your name?” he asked.

“Born in the thick of summer, I was, here at Parnell’s—at your plantation. Mama named me for them two things. Summer Parnell.”

The master nodded.

“The name suits you, Summer. From what I can see, you’ve always been a bright child.”

“Yessir. Thank you, sir.”

I tried to say as little as I had to during these meetings. I worried that I’d disgrace Mama somehow, so the less I spoke, the better. The visits didn’t last long before the master dismissed me. We usually exchanged brief courtesies, got to looking close at each other, then I’d leave.

But this year was different. This year, Master Gideon wasn’t letting me go so fast. He was calling me bright, and talkin about all kinds of things. And before I knew it, he was giving me a gift. He was giving me the gift of his words. The gift of more than the speaking of brief courtesies.

“Do you know why I come to this study, Summer?”

“Its your private quarters, sir. Your room for contemplation, Mama says.”

The master smiled a little smile. “Contemplation.” He nodded. His eyes left mine, but only for a moment. “This study’s where I come to be among my books and papers, and my quill. It’s where I find truths—in the pages of these many volumes.”

Master Gideon turned to the bookshelves that flanked the large arched windows. That was the gift— his words. Truths in the pages of these many volumes. I’d been polishing the master’s books ever since my fingers could hold a rag. Whenever I asked Mama what them books were for, and why the master had so many, she told me to mind my business and to keep with my work. Them books was something she refused to discuss.

But truth, now that was another story. Mama wasn’t shy on talkin’ about truth. Mama said when I was born I had a face like a hooty owl—wide-eyed, and always lookin’. A face searching for truth, even in darkness. I was hooty-eyed still, Mama said. Still searching, I guess. Got eyes the color of clover. Always thought maybe there was truth in everything green and new.

But it wasn’t till that day in the master�

��s study, my eleventh birthday, that the word truth stuck its burrs in me and held on tight And it wasn’t till that same day that my mind put truth and books into the same bailiwick.

The master had said he tried to fetch him some truth in all his pages and papers. But there was another kind of truth in that study, too. Something real and close and right. Something I didn’t fully know. Something unspeakable.

Silence stood between Master Gideon and me. I had let my eyes drop, but I could feel the master’s gaze resting right at my face.

“You’re resembling your mama more and more, Summer.”

“Yessir. I do favor her, sir.”

“That’s lucky, Summer, to look like Kit.”

“Thank you, master.”

My cheeks grew warm, and all of a sudden the collar on my dress started to itch. I’d told Mama the dress was getting too small, that I was growing past its seams, but she had insisted I wear it to see the master. Morning’s heat was swelling fast all around now. The master took a kerchief from his breast pocket. He lifted his spectacles and wiped the bridge of his nose. “August in Virginia can be merciless,” he said.

I went to the windows, tied back the curtains, and unlatched the window toggle to let in some air. When I returned to my place near the master’s desk, Master Gideon had turned open what to me looked like a ledger. And he’d taken up his quill. He turned to a clean page of the ledger and showed me its bare whiteness. “I call this book my index of memorable consequences. I write about those things that are most important to me. It’s a record of daily memories, events, and circumstances I want to recount in my elder years.”

The master dipped his quill. “That’s all a fancy way of saying I keep a journal.” He motioned with two fingers for me to come closer to the desk, close enough to see his journal better. All I could think of, again, were the master’s words: truths in the pages of these many volumes.

Master Gideon wrote something at the top of the page. “I always start with the day’s date,” he said.

I watched carefully as the master’s quill curled and scratched on the parchment. “You ever write about Mama?” I asked suddenly.

The master didn’t answer, but I saw his hand flinch just the tiniest bit. He kept his eyes on his quill. He let my question pass like a fly on a breeze. He blew gently on the ink at the top of his page, then closed his journal.

It wasn’t long before Master Gideon was sending me on my way, out into the merciless Virginia heat.

That night, as dusk fell on the quarters, Mama wrapped me in a hug. She thanked heaven for letting her see another one of my birthdays.

“I’m a lucky woman to still have both my children— none of them sold away, none of them beaten, both of them healthy as the shade trees that tower this land,” she said.

But when I showed Mama the birthday present Rosco had given me, a hard look came to her. Mama and I had been butting heads ever since I could remember. The older I got, it seemed, the more we disagreed on things. There were times when we threw some heated words at each other, Mama and me. Tonight, when I saw the frown pinching Mama’s face, I knew right away my book was going to put us at odds.

“Gideon give you that?” she wanted to know.

“Rosco,” was all I said.

Mama shook her head. “Don’t tell nobody ’bout that thing, Summer. Don’t even speak to the leaves about it, you hear me?” she warned.

“How come I can’t?”

“’Cause if the wrong people find out you got a book, you’ll be sold off, or worse.”

“What wrong people? Master Gideon ain’t never gonna know. He don’t hardly take notice on me— except on my birthday. Other times he don’t even know I’m alive.”

“He knows,” Mama said firmly.

“If it ain’t my birthday, he don’t so much as look my way.”

“He’s busy running this plantation, is all.”

I fingered the pages of my book. “Does the master call you to him on your birthday?” I’d never thought to ask Mama that before, but now it seemed such a sensible question.

“No,” Mama said.

“How come?”

“He don’t know when my birthday is,” she said softly.

“Why don’t you tell him—then he’ll know.”

Mama folded her arms tight. “Hush up,” she said.

“You’re always trying to hush me.”

“That’s ’cause you’re a bottomless well of questions, child. You run too deep with too many how-comes and why-nots. It’s a pestering menace.”

I was holding my book close to me now. As close as breathing, it seemed.

“I just don’t want you to make a silly mistake and go bragging to folks about that thing. You know how talkedy you can get.”

I didn’t tell Mama that Rosco had promised to learn me letters, had promised to learn me to read with the book he’d stolen from young Master Lowell.

Rosco was the only one of us who had been learned to read. “That boy knows way too much for a thirteen-year-old child,” Mama says.

Rosco taught himself to know words. He did it by listening to Lowell, Master Gideon’s boy, practicing his lessons. You see, Rosco was Lowell’s own body servant; Rosco belonged to Lowell. He polished Lowell’s shoes, shined his door brass, put Lowell’s bedwarmer between his sheets when the colder months came on, mucked the stall where Dash, Lowell’s gelding, stayed, and did any other chores Missy Claire, the master’s wife, wanted him to do for Lowell.

It wasn’t regular for a boy to have a slave child of his own. Heck, Lowell couldn’t have been no more older than Rosco—twelve, maybe thirteen years old. But I heard Mama tell her friend Thea that Master Gideon gave Rosco to Lowell because Lowell was sickly. He had some kind of breathing trouble, which was why he was always wheezing like a pup, hungry for air. Lowell’s wheezy breathing could have been why he was so skinny—and so pale.

Anyway, ever since Miss Rose McCracken, the white teacher lady, had been coming to Master Gideon’s study to learn Lowell to read, Rosco had been stealing looks at Lowell’s lesson books. Rosco said whenever he could hear Lowell reading out loud, he listened real close. Then later, when Lowell was out in the courtyard taking his afternoon refreshment, Rosco looked at Lowell’s lesson books and, one by one, had learned the letters for himself. Rosco said he first started doing this two summers ago.

When I asked Rosco how he learned so good, he said it took him many days of quick, eye-dartin’ glances before he began to catch on, and more time on top of that before he could fully read. He said the dim light of Lowell’s room forced him to look real hard at them letters till they started to make sense—till they grew into full-out words.

Well, once, after Lowell was done with one of his lesson books—Rosco said it was a book called The Clarkston Reader— Lowell set it on the shelf in Master Gideon’s study. One day Rosco swiped the book right off the shelf, slid it under his shirt, brought it back to the quarters, and taught himself to read it full and well—from the very front to the last page!

Then Rosco got the boldness of a bloodhound in him, swiped himself a page from Lowell’s writing tablet, and learned himself to make letters.

When Mama found out Rosco had stolen from the master’s son, she begged him to put the stuff back. Her eyes had tears in them—that’s how serious she was about it. But Rosco, he said no. He went against Mama, just like that.

By the time night fell, the dander had settled between Mama and me. Mama said, “I know we have our share of clashes, Summer. And I have true concern about that book. But I’m not one to deprive a child of her birthday present. You can have the book so long as you promise to keep it hid away.”

“I promise, Mama,” I said.

Later, after everyone had gone to sleep, Rosco came close to my pallet and whispered to me, “Now it’s your turn, Summer. It’s your turn to learn letters, and I’m gonna teach you. That’s your real birthday present from me—from your brother Ros, the smartest slave boy on Pa

rnell’s place.”

Then Rosco tucked Lowell’s hard, thin book under my head. “Dream big, now,” he said. “We’ll start our lessons soon. Happy birthday, Summer.”

I fell asleep happy and itchin’ to get started with my lessons. But I kept hearing Mama’s warning about my learning book.

“. . . keep it hid away.”

2

Rosco

August 24, 1862

THE BIT.

It’s choking me.

Choking back my breath.

Only breathing I can do is through my nose. But that breathing hurts. It hurts to smell the leather and iron, soaked with the foam from my spit.

Then comes the worst of it. He’s yanking on the bit. Stretching my lips and jaws into an ugly, messed-up grin. Snatching back my neck. Sending my eyes rolling. Rolling bald and blinded, way far back in my head.

I can’t fight the bit. Ain’t never been able to break free from its iron hold.

I get still and quiet. Throat burning. Limbs gone to mush.

He’s ready to mount me, now that I’m still. Mounts me bareback. Doesn’t even bother with the saddle.

My insides are screaming, “Buck! Buck ’im off!” But I’m goose-flesh all over. Helpless.

Soon his face is down near mine. His mouth right at my ear. The breath on him is hot and stinky—like a sick, mad dog, just come from slopping swamp water. Now he’s hollering crazy-like, “Come on, nigra boy, take me for a ride!” His boot heels dig hard into my gut. “Giddy-up!” he shouts. And then he’s riding me full-out.

I try, best I can, to twist my head back around. Try to see his face. But there ain’t no way to twist. He’s got me reined up tight.

I know his voice, though. It’s the ugly voice of slavery. It’s the cruel call of every white man who enjoys his ride on the back of a nigra.

I’m able to see my feet making a slow gallop. My feet are bare. Thick with mud. The longer I look, the more I see they ain’t feet at all. My toes have grown together. They’ve grown hard.

Silent Thunder

Silent Thunder