- Home

- Andrea Pinkney

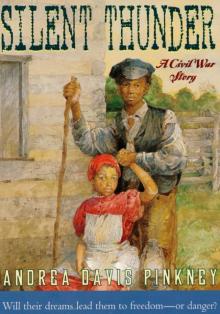

Silent Thunder Page 5

Silent Thunder Read online

Page 5

I was on my way to work ’longside Mama in the cookhouse. The sight of Mama’s scar hadn’t left me. I still had tears snatching at my insides. I was trying real hard to think of other things—to shake the memory, same way I shake the wrinkles from Missy Claire’s table linens—but, deep down, I had a feeling this morning’s sight would stay in my thoughts for a long time coming.

As soon as Rosco and I started walking, Rosco reached in his back pocket and pulled out something that looked like one of Thea’s herb pouches, the kind she presses on bruises and wounds to help them heal.

“Here, Summer,” he said, pushing the pouch into my chest. “It’s a present.”

I held the pouch over toward Rosco’s lantern. “My birthday’s been come and gone for weeks now,” I said, turning over the funny-looking pouch.

“Think of it as an any-ol’-time present,” Rosco said. “I made it for you, Summer. Stuffed and sewed it myself. It’s a dolly.”

I looked at Rosco sidelong. “Since when did you know how to sew?” I asked.

“Since I got me the feeling to make you that dolly.”

Behind us, we could hear the field slaves beginning to spread through the tobacco fields, ready for another long day of picking. Rosco motioned to me. “We better not dawdle,” he said. “Gideon can be real cranky on Sundays. Mama says it’s ’cause he hates going to church.” Rosco had walked a few steps ahead I trailed not far behind as he spoke. “Missy Claire makes Parnell sit in the front pew every week. He sure don’t like doin’ that, and it’s worse when Lowell gets to stuttering his way through the prayers and hymns. That shames Parnell bad, Mama says.” Rosco was picking up his pace. I had to walk double time to keep up. “Master Gideon won’t take kindly to us being late,” he said.

The doll Rosco made me was far from pretty, not like them china-head dolls Missy Claire’s got sitting up on her bed pillows. (Them’s the dolls Missy’s had since she was a child herself, Mama says.)

Rosco’s handmade dolly wasn’t no more than a scrap of burlap from some old flour sack, stuffed with a hump of cotton. Its arms and legs were spruce twigs hitched to the doll’s body so’s they could move.

And that thing wore the funniest little face. A face made from a walnut shell. Its face looked wrinkly, like Thea’s face is starting to look. Wrinkly, but wise, somehow. And the doll’s walnut face was the same color brown as Mama’s face, and my face, too.

“What’s her name?” I asked, bringing the dolly’s skinny twig-arms together and out again, helping her do a hand clap.

“Name her what you want.” Rosco shrugged.

“How ‘bout I name her Walnut, like her face.”

Rosco shook his head, like he was feeling sorry ’bout something. “I wish I could’a got you a china-face dolly, Summer, the kind they make for white girls.”

I was thinking the same thing, but there was a hint of regret in Rosco’s eyes that kept me from saying what was on my mind. Walnut was far from china. Real far. I tried to make Rosco feel better by telling him something I didn’t truly believe. “Them china dolls is too flimsy, anyhow. They break quick as an egg if you drop one. Heck, Walnut here, she’s special. You could drop her a million times over and she’d still be good as new.”

Now Rosco was looking sidelong at me. “You expect me to believe you’re really thinking that’s true, Summer?”

I shook my head. I let go a tiny smile. “Can’t blame me for trying, Ros.” I walked Walnut’s spindly legs out in front of me as if she were walking on the air, walking along with us. “Why’d you make me this doll, anyhow, Ros?” I asked. “This any-ol’-time present?”

“You need a friend you can talk to in private—any ol’ time. Somebody who ain’t got ears for hearing, a mouth for talking back, or the ways of a seer,” Rosco said.

As we approached the house, I could see the light of Mama’s lantern coming from the cookhouse.

Rosco put a firm hand on my shoulder. “Thea told me how you were spouting them letters I taught you— the P and the Q.” He gave me a solid look. “You can’t be doing that, Summer.”

“I can’t help it, Ros,” I said. “I got what Thea says is—”

“I know, Summer. I know about the silent thunder,” he interrupted. “I got it too,” he said softly. “But I don’t go telling everybody.” Rosco pointed toward Walnut with his chin. “I sewed you the dolly so’s you can tell her all I been teaching you. So’s you can let your cat out of the bag in a way that won’t cause no trouble.”

Now I was holding Walnut to me. She was starting to feel like a friend already. “How do you mean?” I wanted to know.

Rosco gently lifted Walnut from my hold. “Like this,” he said, whispering close to the side of Walnut’s tiny head.

“Looks like you’re saying a prayer to her.”

“I’m prayin’ all right,” Rosco said. “Prayin’ you get knocked with some horse sense.” Rosco’s lips were still pressed close to the place where Walnut’s ear would be if she were a china doll. “I’m showing you how it is you should tell this here dolly what you know,” Rosco said. “Speak to her more quiet than the breeze speaks to the sky. If you do that, Summer, you can speak as much of your mind as you please.”

I had to think on that for a moment. “Can I tell her when I’m feeling squirrely?”

Rosco nodded.

“Can I tell her what I think ’bout Missy Claire and her Arts and Letters Society?”

Rosco nodded again. “You can tell her any deep-down thing you want”

“I got a lot I want to tell Walnut,” I said quietly.

“Good,” Rosco encouraged. “‘Long as you say it so’s only she can hear. Promise me, Summer.”

“I promise.”

Rosco gave my hand a little squeeze.

“Ros,” I asked, “what is arts, anyway?”

Rosco thought a moment. “Arts is a special way of doing something, making something fine as can be. Like Mama’s way of shaping tea cakes. And Clem’s way of shoeing horses. That’s arts,” Rosco said.

We were at the front steps of the house now, about to go inside, about to face our work for the day.

But I was too squirrely to work. I twirled Walnut by her arms. Spun her out in front of me to make her dance. Then, like a cricket springing free from under a leaf, I asked Rosco, “You ever wonder why we ain’t got no pa?”

“Everybody’s got a pa.”

I went back to cuddling my dolly. “Who’s our pa, then?”

Rosco’s jaw went tight. “Somebody,” was all he said.

“Somebody who? And where’s he at?”

Rosco kicked at the steps in front of him. “Girl, you always got a bees’ nest of questions buzzing up in you. It’s enough to drive a good man to agitation.”

I could smell Mama’s biscuits. “You ever ask Mama ’bout our daddy?”

Rosco kicked at the steps again, harder this time. “Nope,” he said.

“How come?”

Rosco wouldn’t look at me then. He said, “Half the slaves on this place don’t know nothin’ about who their pa is.”

“But don’t you ever wonder, Ros?”

Now Rosco’s jaw was tight as ever. “I ain’t like you, Summer. I ain’t got the same bees bothering me. I don’t want to know the answer to every last little thing.”

“But this ain’t little, Ros.”

Rosco went around to the side door of the house. Before he walked up the back steps to Lowell’s room, he said, “Summer, if you mess with too many bees, you come away with a bad sting.”

I cradled Walnut, listening to Rosco creak his way up the stairs, wishing I’d remembered to ask him about his own silent thunder.

10

Rosco

September 28, 1862

I LOVED SUNDAY MORNINGS at the house, when the Parnells had gone to church. It was quiet, and I could take a moment to watch the sun stretch its arms along the walls of the master’s study.

Today, lady sun was doing a fine job dan

cing across Master Parnell’s writing desk. And she did me a true favor by calling my attention to the Harper’s Weekly that was folded open and resting on the desk blotter.

I leaned over the desk, just enough to see a headline and a good bit of the main story. My eyes followed down the page. I spotted President Abraham Lincoln’s name right away. Then I came to two words I didn’t know. Two long words I tried to sound out silendy.

Emancipation Proclamation.

The article said the president had presented a draft of this Emancipation Proclamation to Congress, and that he intended to issue a formal version of the document at the first of the new year, 1863. This document would call for the freedom of all slaves.

Right then, something flinched inside my chest. I read the final sentence again, letting my eyes rest on each word. I had to make sure I was reading them right.

I got a little hum up inside me; a strange, eager feeling. The same excitement I got whenever I rode Dash at a sprint in the far meadow. It was a feeling I didn’t fully understand, but I sure liked the way it swelled in my belly. I had to will my insides to be still.

The freedom of all slaves.

Them words were easy. I didn’t even need to sound them out.

But the longer words— Emancipation Proclamation— still snagged in my throat. They were the kind of words that set me a challenge. A challenge that wouldn’t let me step away without giving it a good go.

I sounded them two long-lettered words over and over till I could hear myself pronouncing them outright. When I spoke the words slowly, I could feel my lips and tongue get a hold of them.

Emancipation Proclamation.

Soon I was reading them words smooth as butter, reading them like they were a song, almost.

That’s when I heard Mama calling my name.

She was hollering full-out, scared and shaky. A holler I ain’t never heard come from Mama. “Rosco!”

I quickly put the Harper’s Weekly back like I’d found it and hurried to the front entry, where Mama and Clem were hoisting Master Gideon off the drive-seat of his carriage. Summer stood by, holding Walnut close to her chest. Missy Claire and Lowell were still inside the carriage. Missy’s shoulders were curled in around her. Her whole face was buried in both hands. Lowell was carefully lifting pieces of hair away from his mother’s cupped fingers.

Thea came running from the well at the side of the house, holding a dipper of water. Clem and Mama set Master Gideon out on the grass beside the entry road. He lay flat on his back, his belly sagging. He was bloated and babbling things none of us could understand. His eyelids fluttered when he tried to speak.

Thea knelt beside him. She lifted his head, parted his lips, and tried to help him take in some water. But it was no use. The master couldn’t drink. The water spilled from the sides of his mouth and dribbled down his front.

Thea looked from Clem to Mama to me. Worry clenched her face. “Want me to bring some cayenne liniment?” I asked Mama.

Mama shook her head once. “No, child,” she said, “liniment won’t help this.”

11

Summer

September 29, 1862

YESTERDAY, WHEN THE PARNELLS came home from church, the master was in an awful way. Somethin’ bad had happened to him. Somethin’ I ain’t never seen or known about. The master’s body was two ways at once: limp as gooseflesh, and stiff as a barn door. I would’ve sworn the master was dead, with the way Mama and Clem had him laid out on the grass.

But Parnell didn’t look as though he was gonna let anything or anybody take him from this life. Even in his helplessness, he wore a stubborn expression.

He was talkin’ gibberish. But if I’d had a cent to my name, I’d have bet he was giving an order— “Leave me alone.”

At Mama’s insistence, Rosco loosened the cravat that had become twisted at the master’s neck. The master’s pits and front were soaked with sweat. That’s how I truly knew that he was nowhere near dead. I ain’t never known a dead person to speak or sweat or protest the way Gideon Parnell was doin’ under the high afternoon sun.

Soon after, Doc Bates rushed up in his wagon. He pressed his fingers to the spot where Master Gideon’s ear meets his neck and, right then, the doctor told us all who were standing there that the master had suffered “an apoplectic stroke.” Doc said he’d only seen a few cases of what he called “apoplexy,” and that we could expert the master to “wither in his limbs” and “lose the abilities of articulation.”

Them words didn’t mean nothing to me when Doc Bates said them. But I knew by the way Missy Claire was shuddering and choking on her tears that what the master had was a real bad thing. And I heard her tell Doc Bates that Gideon’s own pa had suffered something similar, before he’d died and left the Parnell plantation to Gideon.

That night, back at the quarters, everybody had something to say about Master Gideon’s stroke—about what was really wrong with him (some disagreed with Doc Bates’s call), and about how we’d all fare now that the master was too sick to run his plantation.

A small group sat around the table and argued. Each person seemed stuck in his or her own belief. And all of us seemed agitated about the day’s happenings.

Thea said Master Gideon had been cursed with what she called “heart-shock,” a wicked condition that didn’t sound too far off from Doc Bates’s description. She explained that one of Master Gideon’s hands and arms and maybe even one of his legs would shrivel and wither like a dead fish. And, Thea told us, Gideon Parnell would come to speak like the sloppy drunks that stagger around the town alleys at odd hours of the night. And that his speech would turn to slur forever, without him even taking a drop of whisky.

Thea spoke with true authority, even more than Doc Bates had. We all listened close, and nobody disagreed. We all Thea spoke, I could see Mama’s lips reciting a prayer.

All the slaves on Parnell’s place stayed up later than usual that night. It was the men, mostly, who sat up debating about what would happen now. I saw Rosco and Clem swapping glances. Me, I held Walnut tighter than ever.

“Missy Claire sure can’t run things,” said Eagan, Parnell’s oldest field slave.

Pippin, who mans the smokehouse, said, “Parnell’s boy, that sickly runt of a child, don’t have nowhere near what it takes to step into his daddy’s shoes.”

Clem stood up when he spoke. He said, “This whole thing is a dream come true for Ranee Smalley, Parnell’s overseer.”

Everybody listened dose to Clem, who was talking in a fury. “You know what they say: ‘When the cat’s away, the mice will play.’ And Ranee is gonna use this as his chance to play—to play like he’s the boss man. Remember how it was whenever Parnell went to Charlottesville for an overnight visit? Rance loved to act like this plantation was all his.”

A few of the men piped up. They were agreeing with Clem.

Mama shushed everybody. “Let’s not jump to all kinds of notions.”

Then Rosco spoke up. “I got me a bit of hearsay,” he said. He looked from me to Mama to Clem. “I got wind that freedom’s comin’,” he said softly.

Several men pulled their chairs closer to the table. “Speak on it. What’s the hearsay?” Pippin gave Rosco a nudge.

I saw Mama listening as close as the men.

Rosco licked his lips. “I hear our very own president has written up a freedom paper.” Now Rosco’s eyes took a moment to look at each and every one of us as he spoke. “He’s puttin together what folks is calling a ‘proclamation’—an order that will set us all free, come the new year.”

Some of the men laughed. “Boy, you been hearin’ tall tales,” said Eagan.

Clem, who was still standing, sat down sharply. “Where you been gettin’ this hearsay, Rosco?”

Rosco was slow to answer. Some of the men leaned in toward Rosco. Finally Rosco said, “I get hearsay same way as anybody else: from keeping my ears cocked and my eyes open.”

Late into the night, when Mama and me finally settled on

to our pallets, I took comfort in Walnut’s tiny brown body and in my Clarkston Reader. I kept my lantern burning low, close to my pallet, so’s I could see my book.

That’s when, all of a sudden, Mama scolded me. “Snuff that lantern, child—snuff it now. And put that wretched foolishness away, you hear.” Mama was whispering with a sure force. Even in the dimness, I could see her anger.

I knew arguing was no use, though I tried. “But Mama, I’m—”

“Don’t give me sass, Summer,” she snapped. “I’m a tired woman tonight. We’ve had enough bad fortune come to this plantation for one day, and we don’t need no more. I told you to keep that book hid away, and I told Rosco the same about any books he gets his hands on. But Rosco, he ain’t like you—he knows better than to be waving a stolen book around.”

I wanted to tell Mama that I had me a silent thunder, and that everyone—even her—had one, too. And that letters were beautiful, fancy things. But Mama wasn’t hearing me, not tonight. I slid my book closer to me. “Mama, I’m not waving it around,” I said

But faster than I could blink, Mama snatched the book from my hands. Thankfully, none of the pages tore, though something inside me was ripping fast. Mama spoke her final words. “Child, this is the wrong night for talkin’ back to your mama. This blasted book is gonna stay with me from here on. You ain’t got no more use for it.”

“I do have use for it!” I snapped. “Why you gotta take it now?”

Mama spoke firmly. “I’m takin’ it now so’s we don’t risk any trouble from here on in. With Gideon’s heart-shock, there’s gonna be all kinds of white folks comin’ round here. Surely, we’ll have visitors—friends of the Parnells—and just plain nosy people from town who want to see for themselves what’s happening now that Gideon’s sickly. This plantation is gonna be swarming with white folks soon as tomorrow. The last thing I need is for you to go around flauntin’ a book.”

Silent Thunder

Silent Thunder